Most discussions of Ada Lovelace begin by mentioning that she was Byron's daughter and that her parents scandalously separated. What's really astonishing in the context of the period is that her mother got custody of Ada. Children were considered property belonging to their fathers in 19th century England. In this case, it came down to the fact that Ada's mother, Lady Anne Isabella Milbanke known as Annabella to her friends, came from a wealthy family and Byron was debt-ridden. Debt was a major motivation for his marriage. So it seemed to me that Annabella's family was in a good position to buy justice for their daughter. It's probably just as well because the only time Byron did have custody of a daughter, he relinquished his parenting responsibility by packing her off to a convent.

Based on Chiaverini's depiction, Annabella wouldn't receive any awards for parenting herself. Yet she should be credited with making certain that Ada followed in her footsteps by pursuing mathematics. This was an extraordinary education for a daughter of the aristocracy. According to the article about her on Wikipedia, Annabella's parents hired a Cambridge professor as her tutor.

If Ada hadn't had Annabella as her mother, it's unlikely that she would have been so advanced mathematically.

In The Enchantress of Numbers, Ada's scientific mentor Mary Somerville told Ada about her conflict with her own parents over her studies. It was widely believed at that time that women's health would be jeopardized by intellectual stimulation. Mary Somerville's experiences caused Ada to appreciate her mother's encouragement of her scientific inclinations. I had never heard of Mary Somerville before I read this book, and was glad of the opportunity to learn about this foremother for woman scientists.

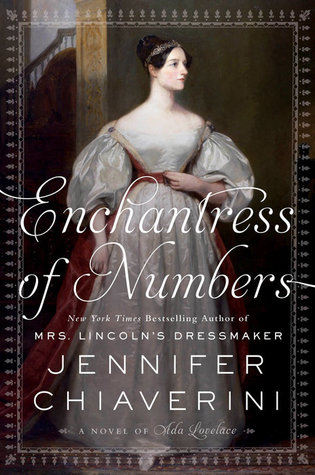

We can't really know about Ada's contribution to Charles Babbage's conceptualization of his proto-computers the Difference Engine and the Analytic Engine. This is a topic that is fodder for speculation for historical novelists like Chiaverini. I made the same argument about Einstein and his first wife in my review of The Other Einstein here. I feel that it's just as legitimate to claim that Ada made a significant contribution as to claim that she made none, and that it was all Babbage's idea. I believe that Chiaverini is persuasive about what she attributes to Ada Lovelace.

Ada's written notes are clearly attributable to her, and they show her to be a woman ahead of her time. The Enchantress of Numbers displays her context. She had influences, and sources of support which do not lessen her achievements. Isaac Newton is quoted as having said, "If I have seen further it is by standing on ye sholders of giants." Jennifer Chiaverini helps us to identify who Ada might have stood on. Yet every designer of a computer algorithm stands on Ada's shoulders because she created the very first such algorithm.